Dead Reckoning

(2018)

Featured in JANE magazine issue seven (2019)

“Summer of 2017, my partner and I left Seattle, where we had lived for seven years, in a 1984 Westfalia Vanagon in search of land that we could cooperatvely steward. Fires were ubiquitous along the entire west coast. Four days into our trip, van troubles began. At first, we could temporarily quell the issues ourselves but new mysterious problems arose and persisted. No mechanic could crack the code; we’d get 100 miles and break down again. We stayed patient, even as life was reduced to obtaining, installing, and testing new van parts. Our longest breakdown happened in Death Valley. We spent long days walking through the desert, listening to the wind rushing through the canyons, and feeling our hot skin grow dry and fragile.

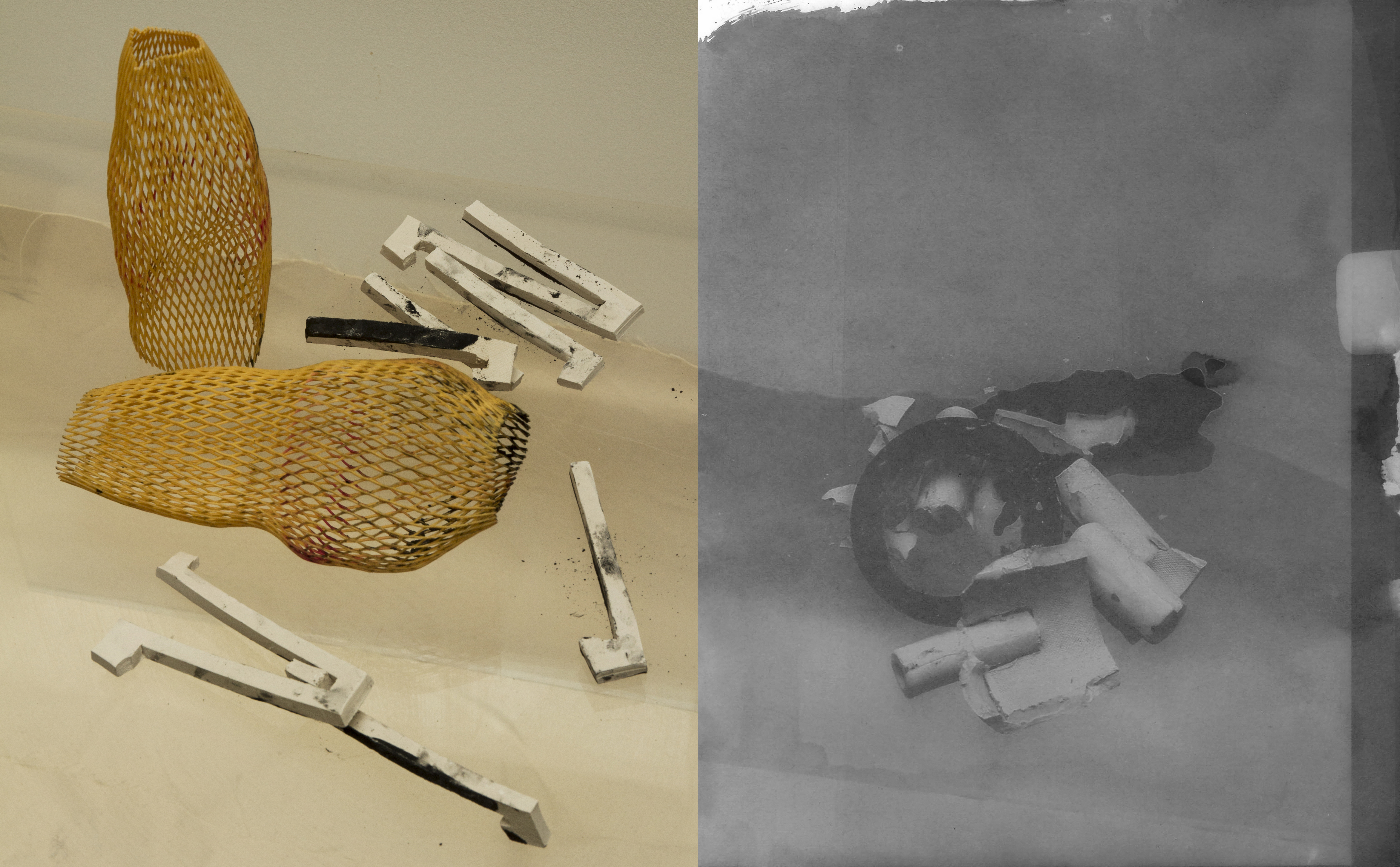

When we finally arrived in Los Angeles, I rendered out of clay, every van part we replaced, and made images of them as archaic vestiges, as if recovered from a fire. This was a wish for a future memory that sometime in the far-off future we might unearth fragments of this toxic early Anthropocene, and these relics might be proof of something catastrophic that we avoided by the skin of our teeth.

Three years later, I was visited by a phoenix in my dreams—a reminder that in order to be reborn, we have to leave paradise and turn our attention to the sun, and the moon, as told in the tale of this mythic bird. We have to let some parts of ourselves die off in order to fertilize new life.

As partly mortal beings supremely dependent on fossil fuels, we are not only feeding the flames that devour our planet, we are also clinging to a false sense of control and comfort. We’re accepting a projection of reality that only temporarily benefits few and will continue to harms most in ways we are only begining to understand. Being entranced by the illusion that we can defy time and space leads is the denial of our own mortality, the denial that we are of the Earth, that we are humans and not gods. In many cultures, we are led to believe that we are above nature rather than a part of it, that it should be bent to our will, and that we are exempt from its laws and cycles.

Being stranded in one of the hottest places in America without typical comforts to cover over the reality of our limits made clear the absurdity of our so called “systems” and made even clearer our unrealised potential to be positive contributors to our planet and good kin to our earth relations.

I intended at some point to make salt prints from the negatives of the original images. I knew they needed to be rendered in a haptic process and that our sun needed to be the central force. These images are born from physicality and landscape; they question the motives of our human-made technologies, the superhuman extensions of our faculties.

The negatives were enlarged and printed on a transparencies, paper was then coated with a mixture of salt and water, the salt-coated paper was taken into a darkroom and coated again with silver nitrate. The transparency was laid over the paper and compressed behind glass before being exposed to full sun. Over time, the light-sensitive silver nitrate darkened to reveal a mirror image of the negative.

Making these prints was partly about illumination and partly about obscuration. They are a lesson I’ve learnt about going into the dark. You go out into the world and take inumerable snapshots of what you’ve found “outside”, but going into the dark to process is what enables the images to reveal their distilled messages. Emerging again and again meet sun is how you make them resound.”